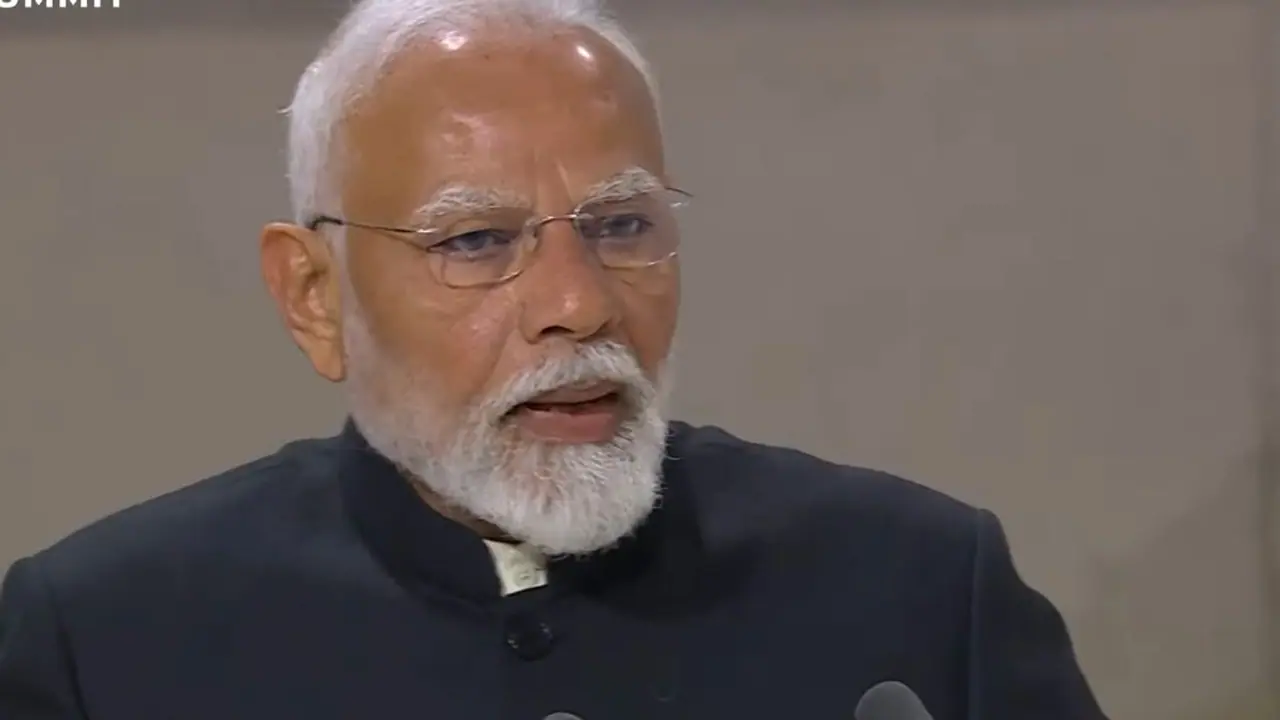

The Delhi University (DU) on Thursday informed the Delhi High Court that while it is willing to present Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s degree records before the court, it will not disclose them under the Right to Information (RTI) Act to what it described as "strangers."

The Delhi University (DU) on Thursday informed the Delhi High Court that while it is willing to present Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s degree records before the court, it will not disclose them under the Right to Information (RTI) Act to what it described as "strangers."

Appearing before Justice Sachin Datta, Solicitor General Tushar Mehta firmly argued against public disclosure, prompting the court to reserve its verdict on DU’s plea challenging a Central Information Commission (CIC) directive. The CIC had previously ordered the university to disclose details related to the Prime Minister’s bachelor's degree.

"DU has no reservation in showing it to the court but can't put the university's record for scrutiny by strangers," Mehta asserted. He emphasized that the CIC’s directive should be quashed, as the "right to privacy" outweighed the "right to know."

The Solicitor General clarified that the university had no intention of concealing anything. "As a university, we have nothing to hide. We have the year-wise record. There is a degree from 1978, Bachelor of Arts," Mehta stated.

The controversy stems from an RTI application filed by one Neeraj, seeking details of all students who appeared for the Bachelor of Arts examination in 1978—the same year Prime Minister Modi reportedly graduated. In response, the CIC, on December 21, 2016, had allowed the inspection of records of all students who cleared the exam that year. However, the Delhi High Court put a stay on this order on January 23, 2017.

Lawyers advocating for the RTI plea argued that disclosing the Prime Minister’s educational credentials served a greater public interest. However, on Thursday, Mehta countered that the "right to know" was not absolute and that personal information, unless directly linked to public interest, remained shielded from disclosure.

Warning against the potential misuse of the RTI Act by "activists," Mehta cautioned that allowing such disclosures would flood the university with similar requests concerning lakhs of its students.

He further argued that the law was never intended for "free people" who merely sought to "satisfy their curiosity" or "embarrass" others.